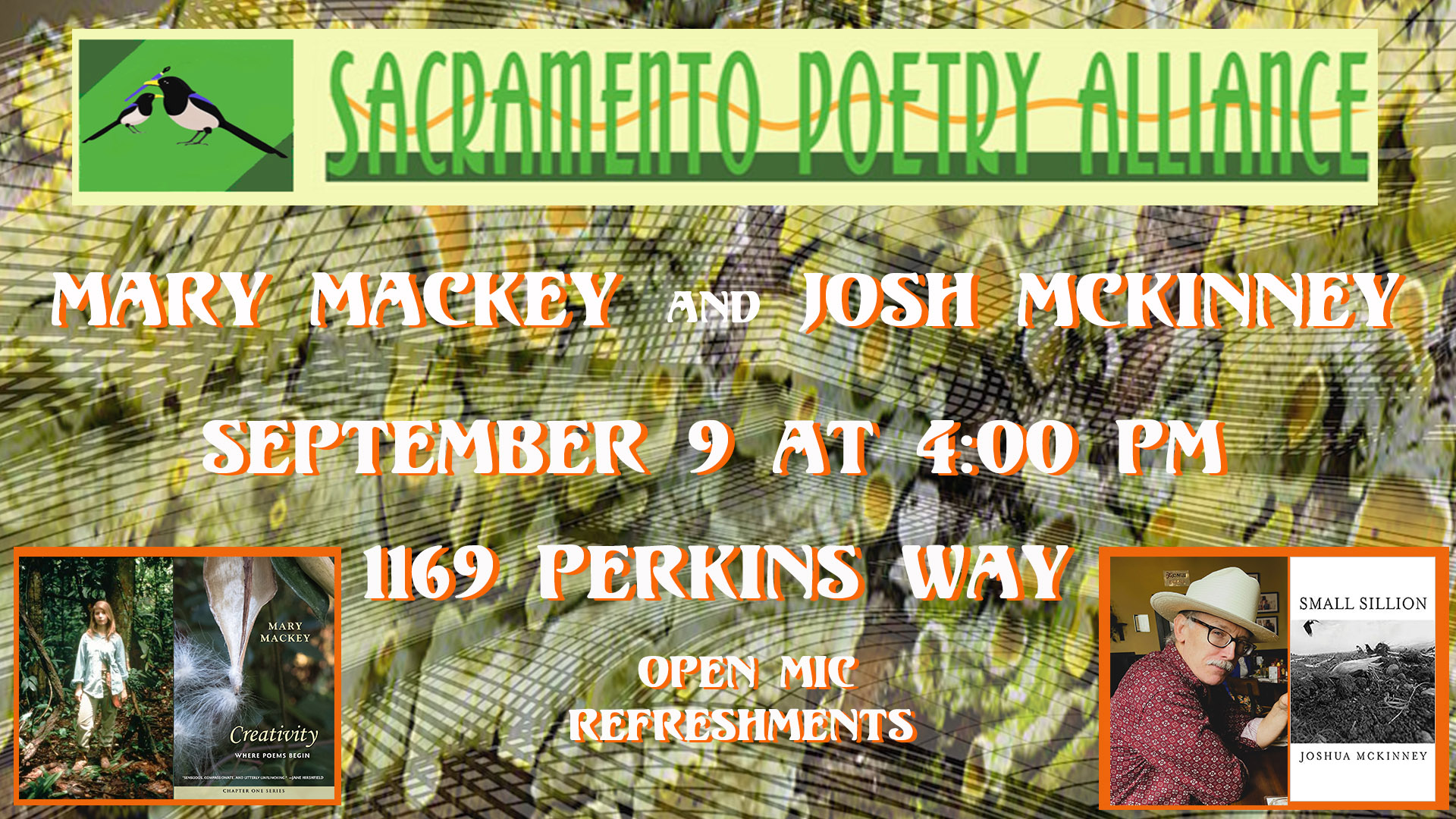

Mary Mackey became a writer by running high fevers, tramping through tropical jungles, being swarmed by army ants, and reading. She is the author of eight poetry collections, including Sugar Zone, winner of a PEN Award, and The Jaguars That Prowl Our Dreams, winner of a Women’s Spirituality Book Award from the California Institute of Integral Studies and the 2019 Eric Hoffer Award for Best Book Published by a Small Press. Her poetry has been praised by Wendell Berry, Jane Hirshfield, D. Nurkse, Al Young, Rafael Jesús González, and Maxine Hong Kingston for its beauty, precision, originality, and extraordinary range. She is also the author of 14 novels including The New York Times bestseller A Grand Passion. Mary taught Creative Writing at CSUS for over three decades until her retirement in 2008. In the early 1970’s she founded the CSUS Creative Writing Program with poet Dennis Schmitz and novelist Richard Bankowsky. Mary’s newest book, Creativity: Where Poems Begin, looks at the origins of inspiration, told in a way that encourages other writers to find their own unique paths to the place where inspiration comes from. Fever Mary Mackey, “105 Degrees and Rising” I nearly died from a high fever just before my third birthday. I remember the experience well, because it was the first time I saw how thin and bright the world could be. I remember lying on a green couch in an over-heated room. It must have been winter, because frost coated the windowpanes, and snow lay on the bare branches of the trees in big lumps. My mother had given me a bottle of Coca-Cola on the principle that I needed to take in more fluids. My temperature must have been somewhere between 106 ͦ and 107 ͦ Fahrenheit, because I was already experiencing that wonderful, detached floating feeling I always get far above 105 ͦ. *** Now enjoying the title of Professor Emeritus, Joshua McKinney teaches half-time at CSUS, where he taught full-time for a quarter century. He resides in the fire-ravaged region known as California, where he spends his time wrangling a pet guinea pig and trying, feebly, to play the five-string banjo. An amateur lichenologist, he is a long-standing member of the California Lichen Society. For the past thirteen years he has served as co-editor, with Tim Kahl, of the online ecopoetics zine, Clade Song. Proselytus The heron has no need of heaven, Fish and frogs attend it, and ducklings the heron lift its vast-winged weight aloft

from The Missouri Review |